|

|

@@ -24,41 +24,52 @@

|

|

|

% 3.2.1 raus

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Compression aproaches}

|

|

|

-The process of compressing data serves the goal to generate an output that is smaller than its input data.\\

|

|

|

-In many cases, like in gene compressing, the compression is ideally lossless. This means it is possible for every compressed data, to receive the whole information, which were available in the origin data, by decompressing it.\\

|

|

|

+The process of compressing data serves the goal to generate an output that is smaller than its input \cite{dict}.\\

|

|

|

+In many cases, like in gene compressing, the compression is idealy lossless. This means it is possible with any compressed data, to receive the full information that were available in the origin data, by decompressing it. Lossy compression on the other hand, might excludes parts of data in the compression process, in order to increase the compression rate. The excluded parts are typicaly not necessary to transmit the origin information. This works with certain audio and pictures files or with network protocols like \ac{UDP} which are used to transmit video/audio streams live \cite{rfc-udp, cnet13}.\\

|

|

|

+For storing \acs{DNA} a lossless compression is needed. To be preceice a lossy compression is not possible, because there is no unnecessary data. Every nucleotide and its exact position is needed for the sequence to be complete and usefull.\\

|

|

|

Before going on, the difference between information and data should be emphasized.\\

|

|

|

% excurs data vs information

|

|

|

-Data contains information. In digital data clear, physical limitations delimit what and how much of something can be stored. A bit can only store 0 or 1, eleven bits can store up to $2^11$ combinations of bits and a 1 Gigabyte drive can store no more than 1 Gigabyte data. Information on the other hand, is limited by the way how it is stored. In some cases the knowledge received in a earlier point in time must be considered too, but this can be neglected for reasons described in the subsection \ref{k4:dict}.\\

|

|

|

+Data contains information. In digital data clear, physical limitations delimit what and how much of something can be stored. A bit can only store 0 or 1, eleven bit can store up to $2^{11}$ combinations of bit and a 1 \acs{GB} drive can store no more than 1 \acs{GB} data. Information on the other hand, is limited by the way how it is stored. What exactly defines informations, depends on multiple factors. The context in which information is transmitted and the source and destination of the information. This can be in form of a signal, transfered from one entity to another or information that is persisted so it can be obtained at a later point in time.\\

|

|

|

% excurs information vs data

|

|

|

-The boundaries of information, when it comes to storing capabilities, can be illustrated by using the example mentioned above. A drive with the capacity of 1 Gigabyte could contain a book in form of images, where the content of each page is stored in a single image. Another, more resourceful way would be storing just the text of every page in \acs{UTF-16}. The information, the text would provide to a potential reader would not differ. Changing the text encoding to \acs{ASCII} and/or using compression techniques would reduce the required space even more, without loosing any information.\\

|

|

|

+For the scope of this work, information will be seen as the type and position of nucleotides, sequenced from \acs{DNA}. To get even more preceise, it is a chain of characters from a alphabet of \texttt{A, C, G, and T}, since this is the \textit{de facto} standard for digital persistence of \acs{DNA} \cite{isompeg}.

|

|

|

+The boundaries of information, when it comes to storing capabilities, can be illustrated by using the example mentioned above. A drive with the capacity of 1 \acs{GB} could contain a book in form of images, where the content of each page is stored in a single image. Another, more resourceful way would be storing just the text of every page in \acs{UTF}-16 \cite{isoutf}. The information, the text would provide to a potential reader would not differ. Changing the text encoding to \acs{ASCII} and/or using compression techniques would reduce the required space even more, without loosing any information.\\

|

|

|

% excurs end

|

|

|

-In contrast to lossless compression, lossy compression might excludes parts of data in the compression process, in order to increase the compression rate. The excluded parts are typically not necessary to persist the origin information. This works with certain audio and pictures formats, and in network protocols \cite{cnet13}.

|

|

|

For \acs{DNA} a lossless compression is needed. To be precise a lossy compression is not possible, because there is no unnecessary data. Every nucleotide and its position is needed for the sequenced \acs{DNA} to be complete. For lossless compression two mayor approaches are known: the dictionary coding and the entropy coding. Methods from both fields, that aquired reputation, are described in detail below \cite{cc14, moffat20, moffat_arith, alok17}.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Dictionary coding}

|

|

|

-\textbf{Disclaimer}

|

|

|

-Unfortunally, known implementations like the ones out of LZ Family, do not use probabilities to compress and are therefore not in the main scope for this work. To strenghten the understanding of compression algortihms this section will remain. Also a hybrid implementation described later will use both dictionary and entropy coding.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

\label{k4:dict}

|

|

|

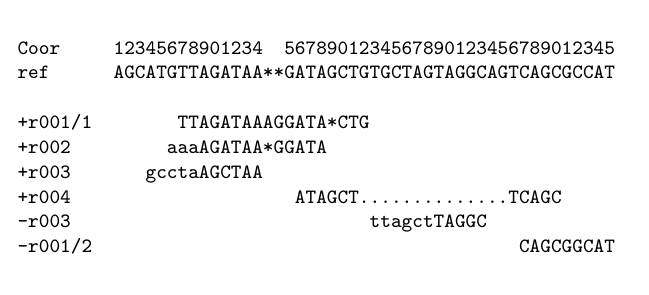

Dictionary coding, as the name suggest, uses a dictionary to eliminate redundand occurences of strings. Strings are a chain of characters representing a full word or just a part of it. For a better understanding this should be illustrated by a short example:

|

|

|

% demo substrings

|

|

|

Looking at the string 'stationary' it might be smart to store 'station' and 'ary' as seperate dictionary enties. Which way is more efficient depents on the text that should get compressed.

|

|

|

% end demo

|

|

|

-The dictionary should only store strings that occour in the input data. Also storing a dictionary in addition to the (compressed) input data, would be a waste of resources. Therefore the dicitonary is made out of the input data. Each first occourence is left uncompressed. Every occurence of a string, after the first one, points to its first occurence. Since this 'pointer' needs less space than the string it points to, a decrease in the size is created.\\

|

|

|

+The dictionary should only store strings that occour in the input data. Also storing a dictionary in addition to the (compressed) input data, would be a waste of resources. Therefore the dicitonary is part of the text. Each first occourence is left uncompressed. Each occurence of a string, after the first one, points either to to its first occurence or to the last replacement of its occurence.\\

|

|

|

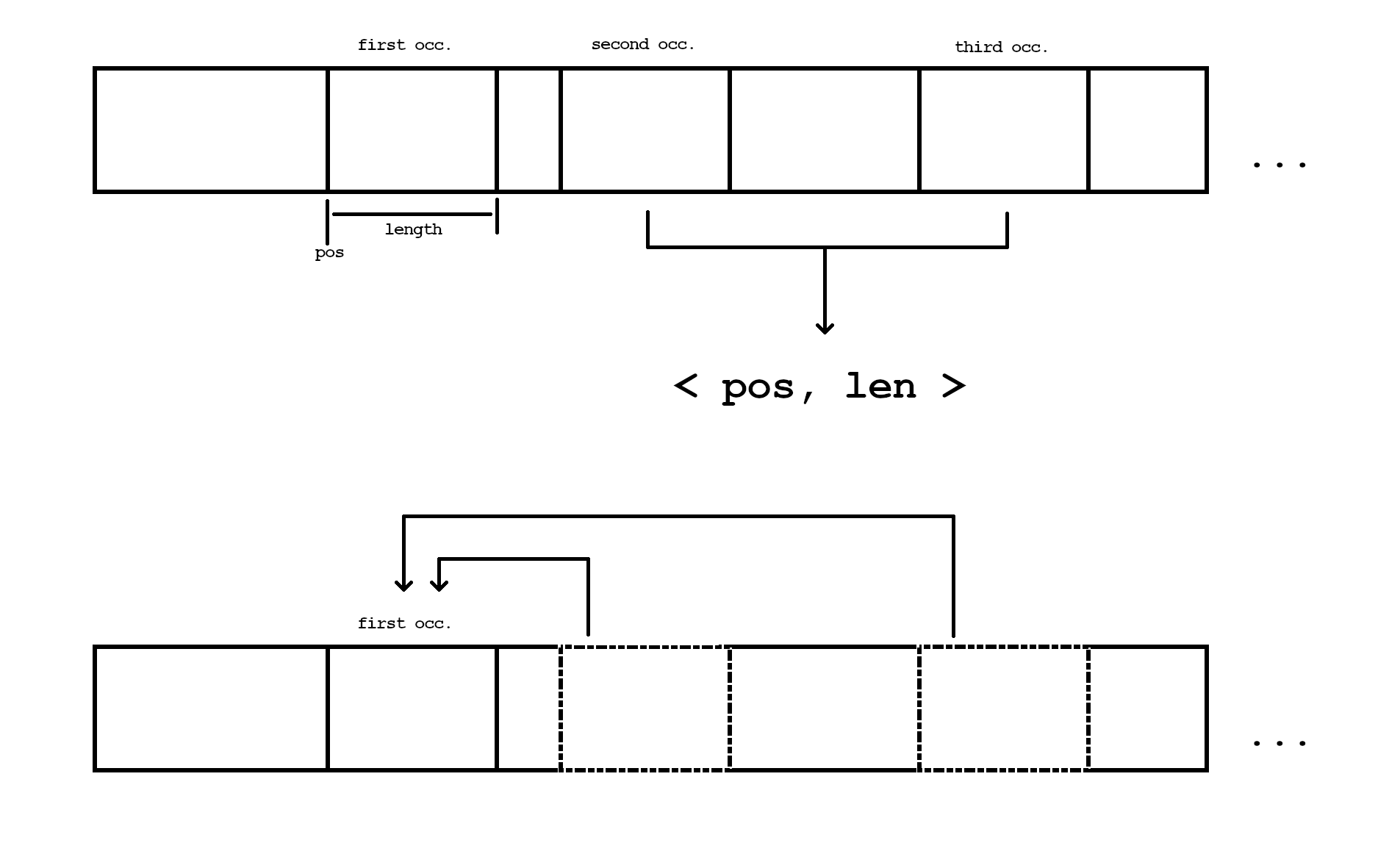

+\ref{k4:dict-fig} illustrates how this process is executed. The bar on top of the figure, which extends over the full widht, symbolizes any text. The squares inside the text are repeating occurences of text segments.

|

|

|

+In the dictonary coding process, the square annotated as \texttt{first occ.} is added to the dictionary. \texttt{second} and \texttt{third occ.} get replaced by a structure \texttt{<pos, len>} consisting of a pointer to the position of the first occurence \texttt{pos} and the length of that occurence \texttt{len}.

|

|

|

+The bar at the bottom of the figure shows how the compressed text for this example would be structured. The dotted lines would only consist of two bytes, storing position and lenght, pointing to \texttt{first occ.}. Decompressing this text would only require to parse the text from left to right and replace every \texttt{<pos, len>} with the already parsed word from the dictionary. This means jumping back to the parsed position stored in the replacement, reading for as long as the length dictates, copying the read section, jumping back and pasting the section.\\

|

|

|

+% offsets are volatile when replacing

|

|

|

|

|

|

-% unuseable due to the lack of probability

|

|

|

-% - known algo

|

|

|

+\begin{figure}[H]

|

|

|

+ \centering

|

|

|

+ \includegraphics[width=15cm]{k4/dict-coding.png}

|

|

|

+ \caption{Schematic sketch, illustrating the replacement of multiple occurences done in dictionary coding.}

|

|

|

+ \label{k4:dict-fig}

|

|

|

+\end{figure}

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\label{k4:lz}

|

|

|

\subsubsection{The LZ Family}

|

|

|

-The computer scientist Abraham Lempel and the electrical engineere Jacob Ziv created multiple algorithms that are based on dictionary coding. They can be recognized by the substring \texttt{LZ} in its name, like \texttt{LZ77 and LZ78} which are short for Lempel Ziv 1977 and 1978. The number at the end indictates when the algorithm was published. Today LZ78 is widely used in unix compression solutions like gzip and bz2. Those tools are also used in compressing \ac{DNA}.\\

|

|

|

-\acs{LZ77} basically works, by removing all repetition of a string or substring and replacing them with information where to find the first occurence and how long it is. Typically it is stored in two bytes, whereby more than one one byte can be used to point to the first occurence because usually less than one byte is required to store the length.\\

|

|

|

-% example

|

|

|

+The computer scientist Abraham Lempel and the electrical engineere Jacob Ziv created multiple algorithms that are based on dictionary coding. They can be recognized by the substring \texttt{LZ} in its name, like \texttt{LZ77 and LZ78} which are short for Lempel Ziv 1977 and 1978 \cite{lz77}. The number at the end indictates when the algorithm was published. Today LZ78 is widely used in unix compression solutions like gzip and bz2. Those tools are also used in compressing \ac{DNA}.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\acs{LZ77} basically works, by removing all repetition of a string or substring

|

|

|

+and replacing them with information where to find the first occurence and how long it is. Lempel and Ziv described restricted the pointer in a range to integers. Today a pointer, length pair is typically stored in two bytes. One bit is reseverd to indicate that the next 15 bit are a position, lenght pair. More than 8 bit are available to store the pointer and the rest is reserved for storing the length. Exact amounts depend on the implementation \cite{rfc1951, lz77}.

|

|

|

+% rewrite and implement this:

|

|

|

+%This method is limited by the space a pointer is allowed to take. Other variants let the replacement store the offset to the last replaced occurence, therefore it is harder to reach a position where the space for a pointer runs out.

|

|

|

|

|

|

- % (genomic squeeze <- official | inofficial -> GDC, GRS). Further \ac{ANS} or rANS ... TBD.

|

|

|

-\ac{LZ77} basically works, by removing all repetition of a string or substring and replacing them with information where to find the first occurence and how long it is. Typically it is stored in two bytes, whereby more than one one byte can be used to point to the first occurence because usually less than one byte is required to store the length.\\

|

|

|

+Unfortunally, implementations like the ones out of LZ Family, do not use probabilities to compress and are therefore not in the main scope for this work. To strenghten the understanding of compression algortihms this section will remain. Also it will be usefull for the explanation of a hybrid coding method, which will get described later in this chapter.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsection{Shannons Entropy}

|

|

|

-The founder of information theory Claude Elwood Shannon described entropy and published it in 1948 \cite{Shannon_1948}. In this work he focused on transmitting information. His theorem is applicable to almost any form of communication signal. His findings are not only usefull for forms of information transmition.

|

|

|

+The founder of information theory Claude Elwood Shannon described entropy and published it in 1948 \cite{Shannon_1948}. In this work he focused on transmitting information. His theorem is applicable to almost any form of communication signal. His findings are not only usefull for forms of information transmition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

% todo insert Fig. 1 shannon_1948

|

|

|

\begin{figure}[H]

|

|

|

@@ -68,8 +79,8 @@ The founder of information theory Claude Elwood Shannon described entropy and pu

|

|

|

\label{k4:comsys}

|

|

|

\end{figure}

|

|

|

|

|

|

-Altering \ref{k4:comsys} would show how this can be applied to other technology like compression. The Information source and destination are left unchanged, one has to keep in mind, that it is possible that both are represented by the same phyiscal actor.

|

|

|

-Transmitter and receiver would be changed to compression/encoding and decompression/decoding and inbetween ther is no signal but any period of time \cite{Shannon_1948}.\\

|

|

|

+Altering \ref{k4:comsys} would show how this can be applied to other technology like compression. The Information source and destination are left unchanged, one has to keep in mind, that it is possible that both are represented by the same physical actor.\\

|

|

|

+Transmitter and receiver would be changed to compression/encoding and decompression/decoding. Inbetween those two, there is no signal but instead any period of time \cite{Shannon_1948}.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shannons Entropy provides a formular to determine the 'uncertainty of a probability distribution' in a finite field.

|

|

|

|

|

|

@@ -88,27 +99,27 @@ Shannons Entropy provides a formular to determine the 'uncertainty of a probabil

|

|

|

% \label{k4:entropy}

|

|

|

%\end{figure}

|

|

|

|

|

|

-He defined entropy as shown in figure \eqref{eq:entropy}. Let X be a finite probability space. Then x in X are possible final states of an probability experimen over X. Every state that actually occours, while executing the experiment generates infromation which is meassured in \textit{Bits} with the part of the formular displayed in \ref{eq:info-in-bits} \cite{delfs_knebl,Shannon_1948}:

|

|

|

+He defined entropy as shown in figure \eqref{eq:entropy}. Let X be a finite probability space. Then $x\in X$ are possible final states of an probability experimen over X. Every state that actually occours, while executing the experiment generates infromation which is meassured in \textit{Bits} with the part of the formular displayed in \ref{eq:info-in-bit} \cite{delfs_knebl,Shannon_1948}:

|

|

|

|

|

|

-\begin{equation}\label{eq:info-in-bits}

|

|

|

+\begin{equation}\label{eq:info-in-bit}

|

|

|

log_2(\frac{1}{prob(x)}) \equiv - log_2(prob(x)).

|

|

|

\end{equation}

|

|

|

|

|

|

%\begin{figure}[H]

|

|

|

% \centering

|

|

|

-% \includegraphics[width=8cm]{k4/information_bits.png}

|

|

|

-% \caption{The amount of information measured in bits, in case x is the end state of a probability experiment.}

|

|

|

-% \label{f4:info-in-bits}

|

|

|

+% \includegraphics[width=8cm]{k4/information_bit.png}

|

|

|

+% \caption{The amount of information measured in bit, in case x is the end state of a probability experiment.}

|

|

|

+% \label{f4:info-in-bit}

|

|

|

%\end{figure}

|

|

|

|

|

|

%todo explain 2.2 second bulletpoint of delfs_knebl. Maybe read gumbl book

|

|

|

|

|

|

-%This can be used to find the maximum amount of bits needed to store information.\\

|

|

|

+%This can be used to find the maximum amount of bit needed to store information.\\

|

|

|

% alphabet, chain of symbols, kurz entropy erklären

|

|

|

|

|

|

\label{k4:arith}

|

|

|

\subsection{Arithmetic coding}

|

|

|

-This coding method is an approach to solve the problem of wasting memeory due to the overhead which is created by encoding certain lenghts of alphabets in binary. For example: Encoding a three-letter alphabet requires at least two bit per letter. Since there are four possilbe combinations with two bits, one combination is not used, so the full potential is not exhausted. Looking at it from another perspective and thinking a step further: Less storage would be required, if there would be a possibility to encode more than one letter in two bit.\\

|

|

|

+This coding method is an approach to solve the problem of wasting memeory due to the overhead which is created by encoding certain lenghts of alphabets in binary \cite{ris76, moffat_arith}. For example: Encoding a three-letter alphabet requires at least two bit per letter. Since there are four possilbe combinations with two bit, one combination is not used, so the full potential is not exhausted. Looking at it from another perspective and thinking a step further: Less storage would be required, if there would be a possibility to encode more than one letter in two bit.\\

|

|

|

Dr. Jorma Rissanen described arithmetic coding in a publication in 1976 \cite{ris76}. % Besides information theory and math, he also published stuff about dna

|

|

|

This works goal was to define an algorithm that requires no blocking. Meaning the input text could be encoded as one instead of splitting it and encoding the smaller texts or single symbols. He stated that the coding speed of arithmetic coding is comparable to that of conventional coding methods \cite{ris76}.

|

|

|

|

|

|

@@ -130,24 +141,28 @@ The coding algorithm works with probabilities for symbols in an alphabet. From a

|

|

|

\end{equation}

|

|

|

}

|

|

|

|

|

|

-This is possible by projecting the input text on a binary encoded fraction between 0 and 1. To get there, each character in the alphabet is represented by an interval between two floating point numbers in the space between 0.0 and 1.0 (exclusively). This interval is determined by the symbols distribution in the input text (interval start) and the the start of the next character (interval end). The sum of all intervals will result in one.\\

|

|

|

+%todo ~figures~

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+This is possible by projecting the input text on a binary encoded fraction between 0 and 1. To get there, each character in the alphabet is represented by an interval between two floating point numbers in the space between 0.0 and 1.0 (exclusively). This interval is determined by the symbols distribution in the input text (interval start) and the the start of the next character (interval end). The sum of all intervals will result in one \cite{moffat_arith}.\\

|

|

|

To encode a text, subdividing is used, step by step on the text symbols from start to the end. The interval that represents the current character will be subdivided. Meaning the choosen interval will be divided into subintervals with the proportional size of the intervals calculated in the beginning.\\

|

|

|

To store as few informations as possible and due to the fact that fractions in binary have limited accuracity, only a single number, that lays between upper and lower end of the last intervall will be stored. To encode in binary, the binary floating point representation of any number inside the interval, for the last character is calculated, by using a similar process, described above.

|

|

|

- To summarize the encoding process in short:

|

|

|

+To summarize the encoding process in short \cite{moffat_arith, witten87}:\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

\begin{itemize}

|

|

|

\item The interval representing the first character is noted.

|

|

|

\item Its interval is split into smaller intervals, with the ratios of the initial intervals between 0.0 and 1.0.

|

|

|

\item The interval representing the second character is choosen.

|

|

|

\item This process is repeated, until a interval for the last character is determined.

|

|

|

- \item A binary floating point number is determined wich lays in between the interval that represents the represents the last symbol.

|

|

|

+ \item A binary floating point number is determined wich lays in between the interval that represents the represents the last symbol.\\

|

|

|

\end{itemize}

|

|

|

% its finite subdividing because of the limitation that comes with processor architecture

|

|

|

|

|

|

-For the decoding process to work, the \ac{EOF} symbol must be be present as the last symbol in the text. The compressed file will store the probabilies of each alphabet symbol as well as the floatingpoint number. The decoding process executes in a simmilar procedure as the encoding. The stored probabilies determine intervals. Those will get subdivided, by using the encoded floating point as guidance, until the \ac{EOF} symbol is found. By noting in which interval the floating point is found, for every new subdivision, and projecting the probabilies associated with the intervals onto the alphabet, the origin text can be read.\\

|

|

|

+For the decoding process to work, the \ac{EOF} symbol must be be present as the last symbol in the text. The compressed file will store the probabilies of each alphabet symbol as well as the floatingpoint number. The decoding process executes in a simmilar procedure as the encoding. The stored probabilies determine intervals. Those will get subdivided, by using the encoded floating point as guidance, until the \ac{EOF} symbol is found. By noting in which interval the floating point is found, for every new subdivision, and projecting the probabilies associated with the intervals onto the alphabet, the origin text can be read \cite{witten87, moffat_arith, ris76}.\\

|

|

|

% rescaling

|

|

|

% math and computers

|

|

|

In computers, arithmetic operations on floating point numbers are processed with integer representations of given floating point number \cite{ieee-float}. The number 0.4 + would be represented by $4\cdot 10^-1$.\\

|

|

|

-Intervals for the first symbol would be represented by natural numbers between 0 and 100 and $... \cdot 10^-x$. \texttt{x} starts with the value 2 and grows as the intgers grow in length, meaning only if a uneven number is divided. For example: Dividing a uneven number like $5\cdot 10^-1$ by two, will result in $25\cdot 10^-2$. On the other hand, subdividing $4\cdot 10^y$ by two, with any negativ real number as y would not result in a greater \texttt{x} the length required to display the result will match the length required to display the input number.\\

|

|

|

+Intervals for the first symbol would be represented by natural numbers between 0 and 100 and $... \cdot 10^-x$. \texttt{x} starts with the value 2 and grows as the intgers grow in length, meaning only if a uneven number is divided. For example: Dividing a uneven number like $5\cdot 10^-1$ by two, will result in $25\cdot 10^-2$. On the other hand, subdividing $4\cdot 10^y$ by two, with any negativ real number as y would not result in a greater \texttt{x} the length required to display the result will match the length required to display the input number \cite{witten87, moffat_arith}.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

% example

|

|

|

\begin{figure}[H]

|

|

|

\centering

|

|

|

@@ -157,14 +172,14 @@ Intervals for the first symbol would be represented by natural numbers between 0

|

|

|

\end{figure}

|

|

|

|

|

|

% finite percission

|

|

|

-The described coding is only feasible on machines with infinite percission. As soon as finite precission comes into play, the algorithm must be extendet, so that a certain length in the resulting number will not be exceeded. Since digital datatypes are limited in their capacity, like unsigned 64-bit integers which can store up to $2^64-1$ bits or any number between 0 and 18,446,744,073,709,551,615. That might seem like a great ammount at first, but considering a unfavorable alphabet, that extends the results lenght by one on each symbol that is read, only texts with the length of 63 can be encoded (62 if \acs{EOF} is exclued).

|

|

|

+The described coding is only feasible on machines with infinite percission \cite{witten87}. As soon as finite precission comes into play, the algorithm must be extendet, so that a certain length in the resulting number will not be exceeded. Since digital datatypes are limited in their capacity, like unsigned 64-bit integers which can store up to $2^64-1$ bit or any number between 0 and 18,446,744,073,709,551,615. That might seem like a great ammount at first, but considering a unfavorable alphabet, that extends the results lenght by one on each symbol that is read, only texts with the length of 63 can be encoded (62 if \acs{EOF} is exclued) \cite{moffat_arith}.

|

|

|

|

|

|

\label{k4:huff}

|

|

|

\subsection{Huffman encoding}

|

|

|

% list of algos and the tools that use them

|

|

|

D. A. Huffmans work focused on finding a method to encode messages with a minimum of redundance. He referenced a coding procedure developed by Shannon and Fano and named after its developers, which worked similar. The Shannon-Fano coding is not used today, due to the superiority in both efficiency and effectivity, in comparison to Huffman. % todo any source to last sentence.

|

|

|

Even though his work was released in 1952, the method he developed is in use today. Not only tools for genome compression but in compression tools with a more general ussage \cite{rfcgzip}.\\

|

|

|

-Compression with the Huffman algorithm also provides a solution to the problem, described at the beginning of \ref{k4:arith}, on waste through unused bits, for certain alphabet lengths. Huffman did not save more than one symbol in one bit, like it is done in arithmetic coding, but he decreased the number of bits used per symbol in a message. This is possible by setting individual bit lengths for symbols, used in the text that should get compressed \cite{huf52}.

|

|

|

+Compression with the Huffman algorithm also provides a solution to the problem, described at the beginning of \ref{k4:arith}, on waste through unused bit, for certain alphabet lengths. Huffman did not save more than one symbol in one bit, like it is done in arithmetic coding, but he decreased the number of bit used per symbol in a message. This is possible by setting individual bit lengths for symbols, used in the text that should get compressed \cite{huf52}.

|

|

|

As with other codings, a set of symbols must be defined. For any text constructed with symbols from mentioned alphabet, a binary tree is constructed, which will determine how the symbols will be encoded. As in arithmetic coding, the probability of a letter is calculated for given text. The binary tree will be constructed after following guidelines \cite{alok17}:

|

|

|

% greedy algo?

|

|

|

\begin{itemize}

|

|

|

@@ -177,7 +192,7 @@ As with other codings, a set of symbols must be defined. For any text constructe

|

|

|

%todo tree building explanation

|

|

|

A often mentioned difference between Shannon-Fano and Huffman coding, is that first is working top down while the latter is working bottom up. This means the tree starts with the lowest weights. The nodes that are not leafs have no value ascribed to them. They only need their weight, which is defined by the weights of their individual child nodes \cite{moffat20, alok17}.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

-Given \texttt{K(W,L)} as a node structure, with the weigth or probability as \texttt{$W_{i}$} and codeword length as \texttt{$L_{i}$} for the node \texttt{$K_{i}$}. Then will \texttt{$L_{av}$} be the average length for \texttt{L} in a finite chain of symbols, with a distribution that is mapped onto \texttt{W} \cite{huf}.

|

|

|

+Given \texttt{K(W,L)} as a node structure, with the weigth or probability as \texttt{$W_{i}$} and codeword length as \texttt{$L_{i}$} for the node \texttt{$K_{i}$}. Then will \texttt{$L_{av}$} be the average length for \texttt{L} in a finite chain of symbols, with a distribution that is mapped onto \texttt{W} \cite{huf52}.

|

|

|

\begin{equation}\label{eq:huf}

|

|

|

L_{av}=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1}w_{i}\cdot l_{i}

|

|

|

\end{equation}

|

|

|

@@ -186,26 +201,84 @@ With all important elements described: the sum that results from this equation i

|

|

|

|

|

|

% example

|

|

|

% todo illustrate

|

|

|

-For this example a four letter alphabet, containing \texttt{A, C, G and T} will be used. The exact input text is not relevant, since only the resulting probabilities are needed. With a distribution like \texttt{<A, $100\frac11=0.11$>, <C, $100\frac71=0.71$>, <G, $100\frac13=0.13$>, <T, $100\frac5=0.05$>}, a probability for each symbol is calculated by dividing the message length by the times the symbol occured.\\

|

|

|

-For an alphabet like the one described above, the binary representation encoded in ASCI is shown here \texttt{A -> 01000001, C -> 01000011, G -> 01010100, T -> 00001010}. The average length for any symbol encoded in \acs{ASCII} is eight, while only using four of the available $2^8$ symbols, a overhead of 252 unused bit combinations. For this example it is more vivid, using a imaginary encoding format, without overhead. It would result in a average codeword length of two, because four symbols need a minimum of $2^2$ bits.\\

|

|

|

-So starting with the two lowest weightened symbols, a node is added to connect both.\\

|

|

|

+For this example a four letter alphabet, containing \texttt{A, C, G and T} will be used. For this alphabet, the binary representation encoded in ASCII is listed in the second column of \ref{t:huff-pre}.

|

|

|

+The average length for any symbol encoded in \acs{ASCII} is eight, while only using four of the available $2^8$ symbols, a overhead of 252 unused bit combinations. For this example it is more vivid, using a imaginary encoding format, without overhead. It would result in a average codeword length of two, because four symbols need a minimum of $2^2$ bit.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\label{t:huff-pre}

|

|

|

+\sffamily

|

|

|

+\begin{footnotesize}

|

|

|

+ \begin{longtable}[ht]{ p{.2\textwidth} p{.2\textwidth} p{.2\textwidth} p{.2\textwidth}}

|

|

|

+ \caption[Huffman example table no. 1 (pre encoding)] % Caption für das Tabellenverzeichnis

|

|

|

+ {ASCII Codes and probabilities for \texttt{A,C,G and T}} % Caption für die Tabelle selbst

|

|

|

+ \\

|

|

|

+ \toprule

|

|

|

+ \textbf{Symbol} & \textbf{\acs{ASCII} Code} & \textbf{Probability} & \textbf{Occurences}\\

|

|

|

+ \midrule

|

|

|

+ A & 0100 0001 & $\frac{100}{11}=0.11$ & 11\\

|

|

|

+ C & 0100 0011 & $\frac{100}{71}=0.71$ & 71\\

|

|

|

+ G & 0101 0100 & $\frac{100}{13}=0.13$ & 13\\

|

|

|

+ T & 0000 1010 & $\frac{100}{5}=0.05$ & 5\\

|

|

|

+ \bottomrule

|

|

|

+ \end{longtable}

|

|

|

+\end{footnotesize}

|

|

|

+\rmfamily

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The exact input text is not relevant, since only the resulting probabilities are needed. To make this example more illustrative, possible occurences are listed in the most right column of \ref{t:huff-pre}. The probability for each symbol is calculated by dividing the message length by the times the symbol occured. This and the resulting probabilities on a scale between 0.0 and 1.0, for this example are shown in \ref{t:huff-pre} \cite{huf52}.\\

|

|

|

+Creating a tree will be done bottom up. In the first step, for each symbol from the alphabet, a node without any connection is formed .\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\texttt{<A>, <T>, <C>, <G>}\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Starting with the two lowest weightened symbols, a node is added to connect both. With the added, blank node the count of available nodes got down by one. The new node weights as much as the sum of weights of its child nodes so the probability of 0.16 is assigned to \texttt{<A,T>}.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

\texttt{<A, T>, <C>, <G>}\\

|

|

|

-With the added, blank node the count of available nodes got down by one. The new node weights as much as the sum of weights of its child nodes so the probability of 0.16 is assigned to \texttt{<A,T>}. From there on, the two leafs will only get rearranged through the rearrangement of their temporary root node. Now the two lowest weights are paired as described, until there are only two subtrees or nodes left which can be combined by a root.\\

|

|

|

-\texttt{<C, <A, T>>, <G>}\\

|

|

|

-The \texttt{<C, <A, T>>} has a probability of 0.29. Adding the last node \texttt{G} results in a root node with the probability of 1.0.\\

|

|

|

-With the fact in mind, that left branches are assigned with 0 and right branches with 1, following a path until a leaf is reached reveals the encoding for this particular leaf. With a corresponding tree, created from with the weights, the binary sequences to encode the alphabet would look like this:\\

|

|

|

-\texttt{A -> 0, C -> 11, T -> 100, G -> 101}.\\

|

|

|

-Since high weightened and therefore often occuring leafs are positioned to the left, short paths lead to them and so only few bits are needed to encode them. Following the tree on the other side, the symbols occur more rarely, paths get longer and so do the codeword. Applying \eqref{eq:huf} to this example, results in 1.45 bits per encoded symbol. In this example the text would require over one bit less storage for every second symbol.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+From there on, the two leafs will only get rearranged through the rearrangement of their temporary root node. Now the two lowest weights are paired as described, until there are only two subtrees or nodes left which can be combined by a root.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\texttt{<G, <A, T> >, <C>}\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

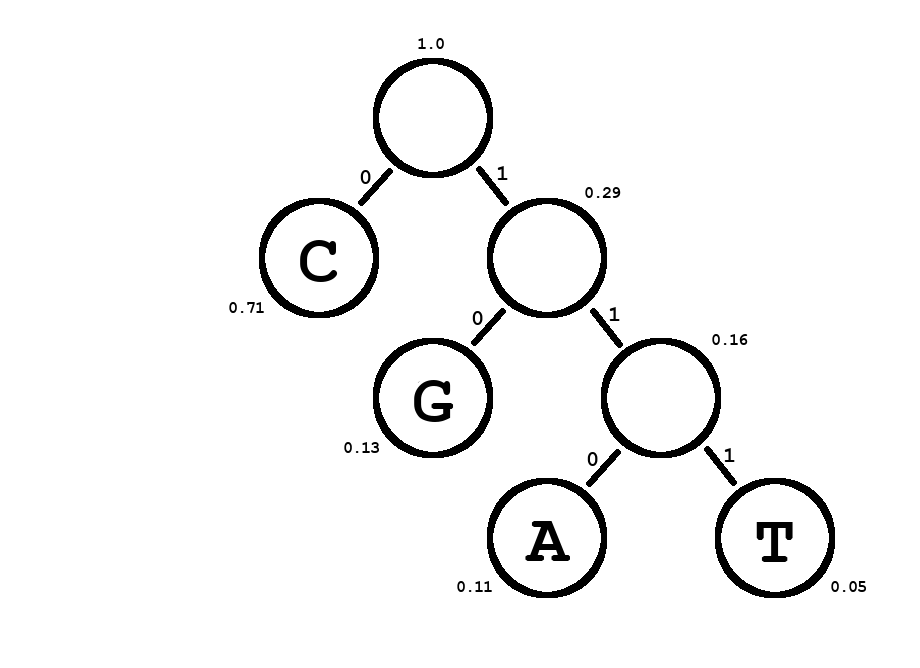

+The \texttt{<G, <A, T> >} has a probability of 0.29. Adding the last, highest weightened node \texttt{C} results in a root node with the probability of 1.0.

|

|

|

+For a better understanding of this example, and to help further explanations, the resulting tree is illustrated in \ref{k4:huff-tree}.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\begin{figure}[H]

|

|

|

+ \centering

|

|

|

+ \includegraphics[width=8cm]{k4/huffman-tree.png}

|

|

|

+ \caption{Final version of the Huffman tree for described example.}

|

|

|

+ \label{k4:huff-tree}

|

|

|

+\end{figure}

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+As illustrated in \ref{k4:huff-tree} the left branches are assigned with 0 and right branches with 1, following a path until a leaf is reached reveals the encoding for this particular leaf. With a corresponding tree, created from with the weights, the binary sequences to encode the alphabet can be seen in the second column of \ref{t:huff-post}.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\label{t:huff-post}

|

|

|

+\sffamily

|

|

|

+\begin{footnotesize}

|

|

|

+ \begin{longtable}[ht]{ p{.2\textwidth} p{.2\textwidth} p{.2\textwidth} p{.2\textwidth}}

|

|

|

+ \caption[Huffman example table no. 2 (post encoding)] % Caption für das Tabellenverzeichnis

|

|

|

+ {Huffman codes for \texttt{A,C,G and T}} % Caption für die Tabelle selbst

|

|

|

+ \\

|

|

|

+ \toprule

|

|

|

+ \textbf{Symbol} & \textbf{Huffman Code} & \textbf{Occurences}\\

|

|

|

+ \midrule

|

|

|

+ A & 100 & 11\\

|

|

|

+ C & 0 & 71\\

|

|

|

+ G & 11 & 13\\

|

|

|

+ T & 101 & 5\\

|

|

|

+ \bottomrule

|

|

|

+ \end{longtable}

|

|

|

+\end{footnotesize}

|

|

|

+\rmfamily

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Since high weightened and therefore often occuring leafs are positioned to the left, short paths lead to them and so only few bit are needed to encode them. Following the tree on the other side, the symbols occur more rarely, paths get longer and so do the codeword. Applying \eqref{eq:huf} to this example, results in 1.45 bit per encoded symbol. In this example the text would require over one bit less storage for every second symbol \cite{huf52}.\\

|

|

|

% impacting the dark ground called reality

|

|

|

-Leaving the theory and entering the practice, brings some details that lessen this improvement by a bit. A few bytes are added through the need of storing the information contained in the tree. Also, like described in \ref{chap:file formats} most formats, used for persisting \acs{DNA}, store more than just nucleotides and therefore require more characters. What compression ratios implementations of huffman coding provide, will be discussed in \ref{k5:results}.\\

|

|

|

+Leaving the theory and entering the practice, brings some details that lessen this improvement by a bit. A few bytes are added through the need of storing the information contained in the tree. Also, like described in \ref{chap:file formats} most formats, used for persisting \acs{DNA}, store more than just nucleotides and therefore require more characters \cite{Cock_2009, sam12}.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

\section{Implementations in Relevant Tools}

|

|

|

-This section should give the reader a quick overview, how a small variety of compression tools implement described compression algorithms.

|

|

|

+This section should give the reader a overview, how a small variety of compression tools implement described compression algorithms. It is written with the goal to compensate a problem that ocurs in scientific papers, and sometimes in technical specifications for programs. They often lack information on the implementation, in a satisfying dimension \cite{sam12, geco, bam}.\\

|

|

|

+The information on the following pages was received through static code analysis. Meaning the comprehension of a programs behaviour or its interactions due to the analysis of its source code. This is possible because the analysed tools are openly published and licenced under \ac{GPL} v3 \cite{geco} and \ac{MIT}/Expat \cite{bam}, which permits the free use for scientific purposes \cite{gpl, mitlic}.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

\label{k4:geco}

|

|

|

\subsection{\ac{GeCo}} % geco

|

|

|

% differences between geco geco2 and geco3

|

|

|

-This tool has three development stages, the first \acs{GeCo} released in 2016 \acs{geco}. This tool happens to have the smalles codebase, with only eleven C files. The two following extensions \acs{GeCo}2, released in 2020 and the latest version \acs{GeCo}3 have bigger codebases. They also provide features like the ussage of a neural network, which are of no help for this work. Since the file, providing arithmetic coding functionality, do not differ between all three versions, the first release was analyzed.\\

|

|

|

+This tool has three development stages. the first \acs{GeCo} released in 2016 \acs{GeCo}. This tool happens to have the smalles codebase, with only eleven C files. The two following extensions \acs{GeCo}2, released in 2020 and the latest version \acs{GeCo}3 have bigger codebases \cite{geco-repo}. They also provide features like the ussage of a neural network, which are of no help for this work. Since the file, providing arithmetic coding functionality, do not differ between all three versions, the first release was analyzed.\\

|

|

|

% explain header files

|

|

|

The header files, that this tool includes in \texttt{geco.c}, can be split into three categories: basic operations, custom operations and compression algorithms.

|

|

|

The basic operations include header files for general purpose functions, that can be found in almost any c++ Project. The provided functionality includes operations for text-output on the command line inferface, memory management, random number generation and several calculations on up to real numbers.\\

|

|

|

@@ -214,10 +287,10 @@ The first two were developed by John Carpinelli, Wayne Salamonsen, Lang Stuiver

|

|

|

The second implementation was also licensed by University of Aveiro DETI/IEETA, but no author is mentioned. From interpreting the function names and considering the lenght of function bodys \texttt{arith\_aux.c} could serve as a wrapper for basic functions that are often used in arithmetic coding.\\

|

|

|

Since original versions of the files licensed by University of Aveiro could not be found, there is no way to determine if the files comply with their originals or if changes has been made. This should be considered while following the static analysis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

-Following function calls in all three files led to the conclusion that the most important function is defined as \texttt{arithmetic\_encode} in \texttt{arith.c}. In this function the actual artihmetic encoding is executed. This function has no redirects to other files, only one function call \texttt{ENCODE\_RENORMALISE} the remaining code consists of arithmetic operations only.

|

|

|

+Following function calls in all three files led to the conclusion that the most important function is defined as \texttt{arithmetic\_encode} in \texttt{arith.c}. In this function the actual artihmetic encoding is executed. This function has no redirects to other files, only one function call \texttt{ENCODE\_RENORMALISE} the remaining code consists of arithmetic operations only \cite{geco-repo}.

|

|

|

% if there is a chance for improvement, this function should be consindered as a entry point to test improving changes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

-Following function calls int the \texttt{compressor} section of \texttt{geco.c}, to find the call of \texttt{arith.c} no sign of multithreading could be identified. This fact leaves additional optimization possibilities and will be discussed in \ref{k6:results}.

|

|

|

+Following function calls int the \texttt{compressor} section of \texttt{geco.c}, to find the call of \texttt{arith.c} no sign of multithreading could be identified. This fact leaves additional optimization possibilities and will be discussed at the end of this work.

|

|

|

|

|

|

%useless? -> Both, \texttt{bitio.c} and \texttt{arith.c} are pretty simliar. They were developed by the same authors, execpt for Radford Neal who is only mentioned in \texttt{arith.c}, both are based on the work of A. Moffat \cite{moffat_arith}.

|

|

|

%\subsection{genie} % genie

|

|

|

@@ -228,7 +301,7 @@ Compression in this fromat is done by a implementation called BGZF, which is a b

|

|

|

\paragraph{DEFLATE}

|

|

|

% mix of huffman and LZ77

|

|

|

The DEFLATE compression algorithm combines \acs{LZ77} and huffman coding. It is used in well known tools like gzip.

|

|

|

-Data is split into blocks. Each block stores a header consisting of three bits. A single block can be stored in one of three forms. Each of which is represented by a identifier that is stored with the last two bits in the header.

|

|

|

+Data is split into blocks. Each block stores a header consisting of three bit. A single block can be stored in one of three forms. Each of which is represented by a identifier that is stored with the last two bit in the header.

|

|

|

\begin{itemize}

|

|

|

\item \texttt{00} No compression.

|

|

|

\item \texttt{01} Compressed with a fixed set of Huffman codes.

|

|

|

@@ -236,13 +309,13 @@ Data is split into blocks. Each block stores a header consisting of three bits.

|

|

|

\end{itemize}

|

|

|

The last combination \texttt{11} is reserved to mark a faulty block. The third, leading bit is set to flag the last data block \cite{rfc1951}.

|

|

|

% lz77 part

|

|

|

-As described in \ref{k4:lz77} a compression with \acs{LZ77} results in literals, a length for each literal and pointers that are represented by the distance between pointer and the literal it points to.

|

|

|

-The \acs{LZ77} algorithm is executed before the huffman algorithm. Further compression steps differ from the already described algorithm and will extend to the end of this section.

|

|

|

+As described in \ref{k4:lz} a compression with \acs{LZ77} results in literals, a length for each literal and pointers that are represented by the distance between pointer and the literal it points to.

|

|

|

+The \acs{LZ77} algorithm is executed before the huffman algorithm. Further compression steps differ from the already described algorithm and will extend to the end of this section.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

% huffman part

|

|

|

-Besides header bits and a data block, two Huffman code trees are store. One encodes literals and lenghts and the other distances. They happen to be in a compact form. This archived by a addition of two rules on top of the rules described in \ref{k4:huff}: Codes of identical lengths are orderd lexicographically, directed by the characters they represent. And the simple rule: shorter codes precede longer codes.

|

|

|

+Besides header bit and a data block, two Huffman code trees are store. One encodes literals and lenghts and the other distances. They happen to be in a compact form. This is archived by a addition of two rules on top of the rules described in \ref{k4:huff}: Codes of identical lengths are orderd lexicographically, directed by the characters they represent. And the simple rule: shorter codes precede longer codes.

|

|

|

To illustrated this with an example:

|

|

|

-For a text consisting out of \texttt{C} and \texttt{G}, following codes would be set for a encoding of two bit per character: \texttt{C}: 00, \texttt{G}: 01. With another character \texttt{A} in the alphabet, which would occour more often than the other two characters, the codes would change to a representation like this:

|

|

|

+For a text consisting out of \texttt{C} and \texttt{G}, following codes would be set, for a encoding of two bit per character: \texttt{C}: 00, \texttt{G}: 01. With another character \texttt{A} in the alphabet, which would occour more often than the other two characters, the codes would change to a representation like this:

|

|

|

|

|

|

\sffamily

|

|

|

\begin{footnotesize}

|

|

|

@@ -258,7 +331,7 @@ For a text consisting out of \texttt{C} and \texttt{G}, following codes would be

|

|

|

\end{footnotesize}

|

|

|

\rmfamily

|

|

|

|

|

|

-Since \texttt{A} precedes \texttt{C} and \texttt{G}, it is represented with a 0. To maintain prefix-free codes, the two remaining codes are not allowed to start with a 0. \texttt{C} precedes \texttt{G} lexicographically, therefor the (in a numerical sense) smaller code is set to represent \texttt{C}.

|

|

|

+Since \texttt{A} precedes \texttt{C} and \texttt{G}, it is represented with a 0. To maintain prefix-free codes, the two remaining codes are not allowed to contain a leading 0. \texttt{C} precedes \texttt{G} lexicographically, therefor the (in a numerical sense) smaller code is set to represent \texttt{C}.\\

|

|

|

With this simple rules, the alphabet can be compressed too. Instead of storing codes itself, only the codelength stored \cite{rfc1951}. This might seem unnecessary when looking at a single compressed bulk of data, but when compressing blocks of data, a samller alphabet can make a relevant difference.\\

|

|

|

|

|

|

% example header, alphabet, data block?

|

|

|

@@ -266,8 +339,18 @@ BGZF extends this by creating a series of blocks. Each can not extend a limit of

|

|

|

|

|

|

\subsubsection{CRAM}

|

|

|

The improvement of \acs{BAM} \cite{cram-origin} called \acs{CRAM}, also features a block structure \cite{bam}. The whole file can be seperated into four sections, stored in ascending order: File definition, a CRAM Header Container, multiple Data Container and a final CRAM EOF Container.\\

|

|

|

-The File definition consists of 26 uncompressed bytes, storing formating information and a identifier. The CRAM header contains meta information about Data Containers and is optionally compressed with gzip. This container can also contain a uncompressed zero-padded section, reseved for \acs{SAM} header information \cite{bam}. This saves time, in case the compressed file is altered and its compression need to be updated. The last container in a \acs{CRAM} file serves as a indicator that the \acs{EOF} is reached. Since in addition information about the file and its structure is stored, a maximum of 38 uncompressed bytes can be reached.\\

|

|

|

-A Data Container can be split into three sections. From this sections the one storing the actual sequence consists of blocks itself, displayed in \ref FIGURE as the bottom row.

|

|

|

+The complete structure is displayed in \ref{k4:cram-struct}. The following paragrph will give a brief description to the high level view of a \acs{CRAM} fiel, illustrated as the most upper bar. Followed by a closer look at the data container, which components are listed in the bar, at the center of \ref{k4:cram-struct}. The most in deph explanation will be given to the bottom bar, which shows the structure of so called slices.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+\begin{figure}[H]

|

|

|

+ \centering

|

|

|

+ \includegraphics[width=15cm]{k4/cram-structure.png}

|

|

|

+ \caption{\acs{CRAM} file format structure \cite{bam}.}

|

|

|

+ \label{k4:cram-struct}

|

|

|

+\end{figure}

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The File definition, illustrated on the left side of the first bar in \ref{k4:cram-struct}, consists of 26 uncompressed bytes, storing formating information and a identifier. The CRAM header contains meta information about Data Containers and is optionally compressed with gzip. This container can also contain a uncompressed zero-padded section, reseved for \acs{SAM} header information \cite{bam}. This saves time, in case the compressed file is altered and its compression need to be updated. The last container in a \acs{CRAM} file serves as a indicator that the \acs{EOF} is reached. Since in addition information about the file and its structure is stored, a maximum of 38 uncompressed bytes can be reached.\\

|

|

|

+A Data Container can be split into three sections. From this sections the one storing the actual sequence consists of blocks itself, displayed in \ref{k4:cram-struct} as the bottom row.\\

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

\begin{itemize}

|

|

|

\item Container Header.

|

|

|

\item Compression Header.

|

|

|

@@ -278,7 +361,9 @@ A Data Container can be split into three sections. From this sections the one st

|

|

|

\item A variable amount of External Data Blocks.

|

|

|

\end{itemize}

|

|

|

\end{itemize}

|

|

|

-The Container Header stores information on how to decompress the data stored in the following block sections. The Compression Header contains information about what kind of data is stored and some encoding information for \acs{SAM} specific flags. The actual data is stored in the Data Blocks. Those consist of encoded bit streams. According to the Samtools specification, the encoding can be one of the following: External, Huffman and two other methods which happen to be either a form of huffman coding or a shortened binary representation of integers. The External option allows to use gzip, bzip2 which is a form of multiple coding methods including run length encoding and huffman, a encoding from the LZ family called LZMA or a combination of arithmetic and huffman coding called rANS.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The Container Header stores information on how to decompress the data stored in the following block sections. The Compression Header contains information about what kind of data is stored and some encoding information for \acs{SAM} specific flags \cite{bam}.

|

|

|

+The actual data is stored in the Data Blocks. Those consist of encoded bit streams. According to the Samtools specification, the encoding can be one of the following: External, Huffman and two other methods which happen to be either a form of huffman coding or a shortened binary representation of integers \cite{bam}. The External option allows to use gzip, bzip2 which is a form of multiple coding methods including run length encoding and huffman, a encoding from the LZ family called LZMA or a combination of arithmetic and huffman coding called rANS \cite{sam12}.

|

|

|

% possible encodings:

|

|

|

% external: no encoding or gzip, bzip2, lzma

|

|

|

% huffman

|